The Bolivian presidential and legislative election originally planned for May 3, 2020 has now been irrevocably fixed to take place on October 18. That decision has been negotiated among the government, Congress, a group of MAS organizations and other civil society organizations, after a period of social and political unrest provoked by the pandemic the country is currently going through. With the certainty that elections will happen, it is time to turn out attention to a long overdue look at election polls, which reveal an intricate as well as surprising process. On the one side, under the first round of elections scenario, the polls show there are three candidacies with good prospects, former Finance Minister Luis Arce (MAS-IPSP), former President Carlos Mesa (CC) and incumbent care-taker President Janine Anez (Juntos). From this trio, the same polls underline Arce’s lead over the other two candidates at the national and regional level as well as across the rural vs. urban divide. On the other side, under the (very likely) assumption of a second round of elections, Arce’s lead seems to evaporate, while Mesa ends up winning the popular vote. Considering the race is populated with many candidates, the pandemic has had a significant impact on the electoral process, and the likelihood for two rounds of elections, the answer to the question of who will be the next president seems to be affirmatively leaning towards the candidate finishing in second place.

Resumption of Elections and the Polls

The Covid-19 pandemic brought the Bolivian 2020 electoral process to a stand still and a state of confusion. The Electoral Tribunal (TSE), the government branch responsible for organizing and carrying out elections, saw several times the need to postpone election day, first from May 3 to September 6 and then to October 18. As far as the TSE, the reason for moving the election date was the health crisis the country has been facing since March, namely the Corona pandemic. The Electoral Tribunal, in its latest argumentation, not only expressed its concern with carrying through elections during the worst phase of the pandemic, but above all, it was alarmed by the possibility that the peak of the infection curve, believed to happen on the first week of September, would coincide with election day. Consequently, and in response to the TSE’s actions and the social unrest ensuing those actions, the Bolivian Congress recently passed a law fixing the day of election and making that date unmovable. Apparently, it saw the need as well to take such a step to assure the election will in fact take place this year. In view of many members of congress, the deferments were intensifying the general perception of political uncertainty, in a country which as recently as October 2019 experienced a fraudulent, and therefore failed, electoral process.

With the certainty elections will happen, the electoral process has re-started. The polls analyzed here were carried out by three officially registered polling companies, Muestras y Mercados, IPSOS and Ciesmori over several months. These companies have actually been conducting polls since the end of last year and are allowed by electoral regulation to continue until a week before election day. This post will concentrate on the period between February and August 2020. According to the law, any company wishing to conduct polls during a Bolivian election process needs to register with the TSE and subject its methodology and results to that institution’s quality control and transparency policies. These polls are then made available to the officially registered media outlets and are published in the TSE’s web site, in a page dedicated to the 2020 elections.

The data presented in the following graphs represent an average of six polls. Considering each poll represents one particular moment in time in the electoral process, it is assumed here that an average of all polls over a period of time takes into account differences among all polls and inherently depicts a trend, which might be a bit more indicative than merely considering the latest poll. In addition, the polls are different, in that they are conducted by different companies, which implies making use of somewhat different questions, different categories such as rural vs. urban or even regional data, as well as different methodologies. However, since the studies have to adhere to TSE standards, they all reflect the intentions of voters towards the candidates, including various scenarios involving a second round of elections between the first and second places, which is what Bolivian law mandates. Lastly, a couple of other candidates were left out of the analysis because they were consistently polling at 1 percent or below.

Scenario 1: First Round of Elections

This first graph depicting average voter intention at the national level distinguishes three groups. One first group includes the three candidates with the largest support. Luis Arce is the leading candidate with an average of 28 percentage points. The other two candidates, Carlos Mesa, who receives an average of 21 percentage points and Janine Anez with 16 points, follow from a short distance. The next group would be made of the undecided and the nobody categories, where the nobody category includes voters who say they will vote for none of the candidates. Assuming that many voters in the nobody group in the end do vote for someone, the two categories together have the potential to make up an average of 20 percentage points representing undecided voters. This is a significant portion of votes in a multi-party system with so many candidates where the level of national support will hardly surpass 30 to 35 percentage points. The third group is made up by the rest of the candidates polling below 10 percent. Luis F. Camacho (Creemos) is the leader of this group with 8 points, followed by the South Corean-Bolivian Chi Hyun Chung (FPV) with an average of 4 percentage points and, lastly, former President Jorge Quiroga (Libre 21) with an average of 2 percentage points.

The graph suggests a seemingly encouraging lead for Arce of 7 percentage points against second placed Mesa and some 12 points against third placed Anez. However, whilst that might seem encouraging to some extent, in a highly volatile political environment such as in Bolivia combined with the current pandemic factor, voter support is subject to change significantly. For that reason, Arce’s situation can be interpreted in two ways. On the one side, it could be encouraging because Arce could still distance himself from Mesa with 2 to 3 percentage points. This would open up the possibility for a direct election. On the other side, it could be discouraging because Arce’s 28 percent is still twelve points away from the all important 40 percent hurdle for the direct election.

That is the reason why the figures for undecided voters and those who are planning to vote for no one becomes relevant. Again, if we assume this group is made up of undecided voters and that a large majority of them decide to vote for one candidate on election day, any one of the first three candidates has a chance at either being elected directly (Arce and Mesa) or getting in the second round scenario. Granted, it is a mathematical chance, but it is not an entirely theoretical one.

The Vote by Departments

Arce’s lead at the national level can be explained when we analyze how voters intend to vote across the nine departments. This can be seen as a regional picture, if you will. The MAS candidate has a significant lead in four of the nine departments, where two of the three largest cities in the country are located. In La Paz, Arce leads the second place candidate by 29 percentage points and in Cochabamba by 21 points. This is not surprising because La Paz and Cochabamba have been significantly supporting MAS since 2005. That level of support has consistently been high, i.e. over the 60 percent level, reaching in La Paz 80 percent in 2009. Important to consider as well is the fact that, according to the National Statistics Institute (INE), La Paz and Cochabamba represent close to 50 percent of the population, where an equally large proportion of the electorate should be concentrated.The other large city, Santa Cruz, represents some 25 percent of the total population, and has tended to vote for the opposition until 2014. Arce also leads in Pando by 15 and in Oruro by 22 points. While Oruro has also been a stronghold of MAS, Pando has voted for the opposition in three general elections prior to 2014. Only in the latter election year has Pando supported MAS.

Mesa’s lead in Chuquisaca and Potosi, 8 and 2 percentage points, respectively, should represent an uphill battle. These two departments have also been MAS departments since 2005. While the support for MAS has been strongest in Potosi, reaching the 70s, support in Chuquisaca has been a bit less, only reaching the mid 50s on average. Albeit this lead can be considered encouraging for Mesa, it is not equal to the commanding leads Arce seems to have in the more populated departments. At another level, however, the race for second place seems to be closest between Mesa and Anez, where the difference seems to be regional, with Anez leading in the lowlands and Mesa in the highlands of the Andes.

On the other hand, even considering the large advantage Arce seems to have over Mesa and Anez in four of the nine departments, that advantage tends to be relative considering that in departments like Santa Cruz and Beni he is polling in the 10 to 15 percentage points range. This is consistent with the historical record. Santa Cruz and Beni are considered the stronghold of the anti-MAS opposition, in fact MAS has never won in Beni, while in Santa Cruz it only recently reached 49 percent of support in 2014. In relation to that, it is also important to consider the more consistent numbers Mesa is getting in the range between 15 to 30 percentage points across the country. This seems to respond to a strategy of slowly but surely solidifying support with the aim at landing in second place.

The Rural vs. Urban Vote

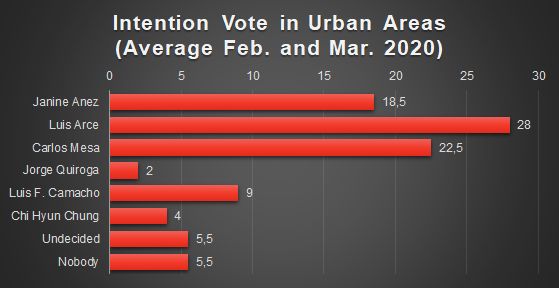

Own elaboration with TSE and Ciesmori data

In accordance to the story painted by the data so far, the first graph above shows that above 45 percent of rural voters intend to vote in favor of the MAS candidate, while the second graph shows in urban areas some 28 percent intend to vote for Arce as well, but this time around Mesa and Anez are well within reach, with 23 and 19 percentage points respectively. These graphs give a similar encouraging picture for MAS, to keep playing a deciding role in Bolivian politics (and perhaps a Morales comeback?). As far as the rural vote is concerned, it does make sense to expect such level of support because the MAS defines itself as a political instrument for the indigenous peoples (i.e. a political party in Bolivian terms). In that sense, it is logical that rural dwellers, who in Bolivia tend to see themselves as indigenous, support the MAS candidate. At the same time, indigenous support for MAS tends to be more diffuse in urban settings. For one, identities seem to get more complex, and, secondly, voter interests are for sure equally complicated. Urban dwellers around the country tend to have multiple alliances with neighborhood associations, unions, trade associations, and a multitude of other groups, all having their own particular interests. The urban vs. rural divide has been a useful approach to try to understand Bolivian society and its voting patterns, because people tend to see themselves as either citadinos (people living in cities) or campesinos (people living in el campo or the countryside).

On the other hand, there are several things to account for when considering the rural vote. To start off, and already partly discussed above, the proportion of people living in the urban areas seems overwhelmingly large in relation to the rural areas. Accordingly, it would be reasonable to deduce that the urban vote weighs substantially more than the rural vote because it tends to concentrate a larger proportion of the electorate. According to the INE, around 70 to 75 percent of the Bolivian population lives in urban areas, in large, medium and smaller cities, while 25 to 30 percent lives in rural areas. A small municipality in the country starts with 5 to 10 thousand inhabitants, and the largest cities such as La Paz and Santa Cruz host a couple of million people. Another thing to keep in mind is that in rural areas the act of voting is per se more difficult, for administrative, logistical, geographical and infrastructural reasons. In that sense, we are led to conclude the significant lead Arce has in rural areas is not as commanding as it appears.

In my opinion, the most likely scenario is the second round of election, rather than negotiations and agreements among the various alliances, which has happened all too often in Bolivia. In a second round, the electorate will have to take sides among two sides, and the data shows Mesa has the better cards.

Scenario 2: The Second Round

To consider this second round scenario, we need to remember what law nr. 26 of 2010 (known as the electoral regime) mandates. The law says the direct election (i.e. no second round) of the President and VP will be determined according to two conditions. First, the candidates will be directly appointed if they obtain 50 percent + 1 of the votes. Second, in the case the winner pair does not get the necessary majority, it can still win if it gets 40 percent + 1 and the second pair in line is more than 10 percentage points behind. A second round of elections within 60 days becomes necessary if neither of the above happens. The President and VP is then elected among the first and second pair of candidates with the most votes.

The picture the graph above gives us is as interesting as it is surprising. Under a second round of elections scenario the winner would be Carlos Mesa. So far, the data has given us an impression that Luis Arce had the potential to win. However, we have also seen that win depends heavily on him being able to increase his level of support to reach more than 40 percent of the national vote as well as increasing his lead to more than ten percent from the second place. That would deliver him the direct election. If this graph above shows the outcome of the elections, in a second round, Arce’s eight point lead at the national level would have evaporated, and instead Mesa would have gained support to win the election with some five percentage points.

The most logical explanation under these conditions seems to be to account for the undecided votes. However, we also have to remember that in a second round voter allegiance will have to be allocated among the candidates left in the race. That is what seems to be happening in the graph above. Many people who were voting for Anez and the other candidates, other than MAS, seem to change their voter preference in favor of Mesa. However, that is not all.

What happened?

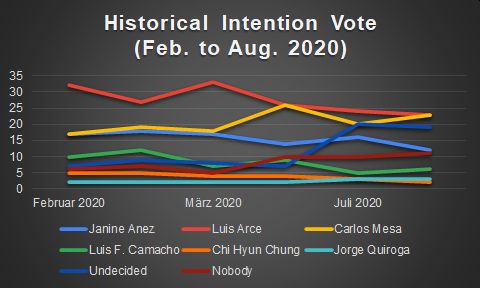

One tentative answer might be depicted in the above graph. If we consider a historical view of the polls from February until August, we can trace the path of support for a candidate. According to the graph, the support for Luis Arce has been steadily declining from a high of 32 in February to 23 in August. Such decline can be explained with the most recent road blockades, demonstrations and strikes many groups within MAS have been organizing. Among those groups, many have been ignoring the restrictions implemented to deal with the pandemic. This has been largely viewed as contributing to an increase in infection numbers in some MAS dominated areas such as El Alto and parts of La Paz, Cochabamba and Santa Cruz. At a time when many people long for stability in order to deal with the pandemic, MAS ally groups have been taking actions that make them look like the ones worsening the pandemic, instead of constructively addressing the situation. What is more, aside from alienating the general public, the actions taken by MAS organizations are provoking negative reactions within the MAS itself. In recent days, there have been many groups either outright decrying those actions, openly criticizing them, openly disavowing some leaders, or other organizations having decided to retract any support they have pledged to MAS. These divisions have become especially visible in the city of El Alto. All these actions and reactions have placed Arce in an uncomfortable place where he has had to endure severe criticism as well as being confronted with difficult questions, such as, what is more important, life or politics? Finally, the current surge in news about Evo Morales’ private life, among them, his perceived wealthy lifestyle in Argentina, and his alleged love affairs with young women (some reports speak of minors), are damaging even more the image of that political organization.

In contrast, Carlos Mesa has been holding steady and largely avoided too many faux pas. He has not only managed to increase in percentage points from 17 percent in February to tying Arce at 23 percent, but, more importantly in this situation, has managed to maintain the level of support across the country. While he shortly irritated the media by “intransigently” demanding the government to carry on with the elections despite an increase in positive covid-19 cases, his rhetoric has largely concentrated on issuing moderate calls for the pandemic restrictions to be respected and for serenity in the political arena.

In the case of Janine Anez, she initially profited from her government’s response to the pandemic, where the country went into strict lockdown and the cases remained low. Between February and March, 17 to 18 percent of the voters said they were willing to vote for her. However, as her government sought to follow a mixed strategy of opening some areas while maintaining restrictions in others, it only seemed to add to the general confusion, leading to social unrest, which at the same time resulted in an increase in the number of infections. As the situation is currently getting worse, with the number of positive cases and deaths reaching large proportions, Anez’s support has faded to 12 percent in August. In addition, a case of corruption where some officials bought malfunctioning breathing machines as well as other Chinese machines which are not working properly anymore, are still damaging the image of her government. One factor affecting her chances all along has been the fact that she decided to run for office. According to a large part of the population, she should not run, she should concentrate instead on delivering the elections. Something that has not been happening, according to the opposition.

One last factor to keep in mind is the number of undecided people, which has been increasing as the elections approach from single digits in February to double digits in August. This has been typical of Bolivian elections. Many people tend to wait until days before the election or until election day to make up their minds. In addition, many people do not want to say for whom they will vote. In Bolivia the vote is secret by law and many people take that all too seriously. Instead of saying I do not want to say, many simply say I do not know or I will vote for nobody. However, this portion of votes might be important in a scenario where a couple of percentage points can decide whether a candidate is elected directly or there is a second round of elections.

In my opinion, the most likely scenario is the second round of election, rather than negotiations and agreements among the various alliances, which has happened all too often in Bolivia. In a second round, the electorate will have to take sides among two sides, and the data shows Mesa has the better cards.

Annex

Table 1: Departments where MAS won since 2002 until 2014, with percentages

You must be logged in to post a comment.